Reflections: Movies that Matter 2025 – showcasing Phoenix of Gaza XR

*In memory of Yahya Sobeih

Between March 22nd – 27th, our project team participated in the Movies that Matter film festival in The Hague, Netherlands, where we presented Phoenix of Gaza XR, a Virtual Reality installation. Movies that Matter aims to “broaden views on human rights” by using film as a medium to encourage discussions on justice, sustainability, and human rights. Established in 1995, the festival also functions as an international hub for individuals and organizations interested in creating human rights-focused film festivals in their own countries. Given this commitment to human rights storytelling, we felt that Movies that Matter was a fitting venue to host a screening of Phoenix of Gaza XR.

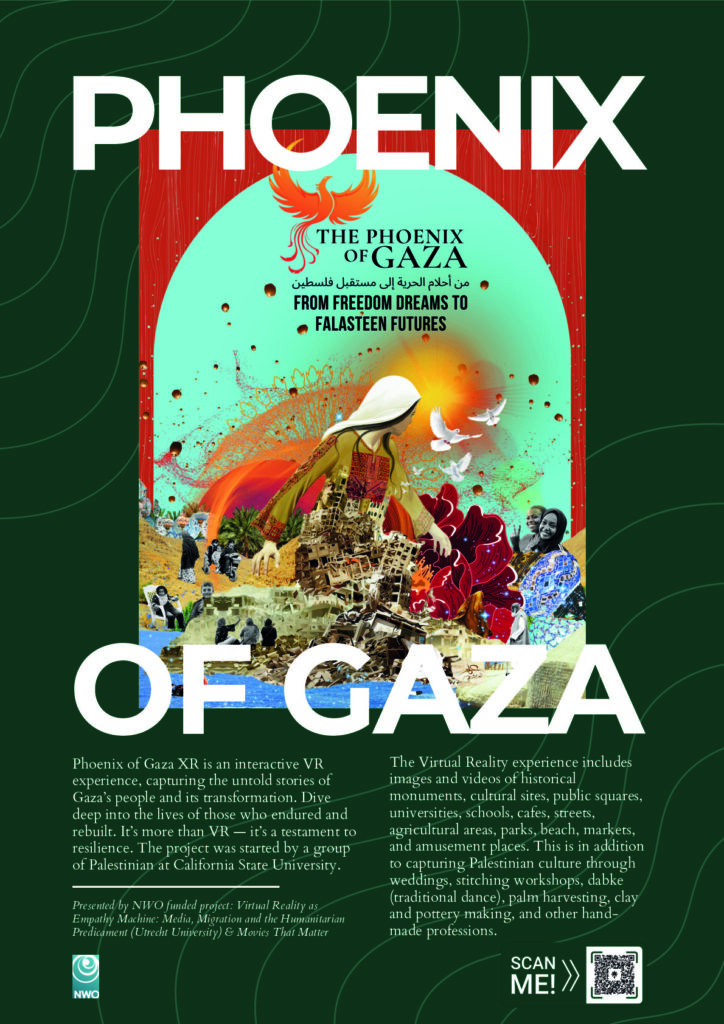

Phoenix of Gaza XR

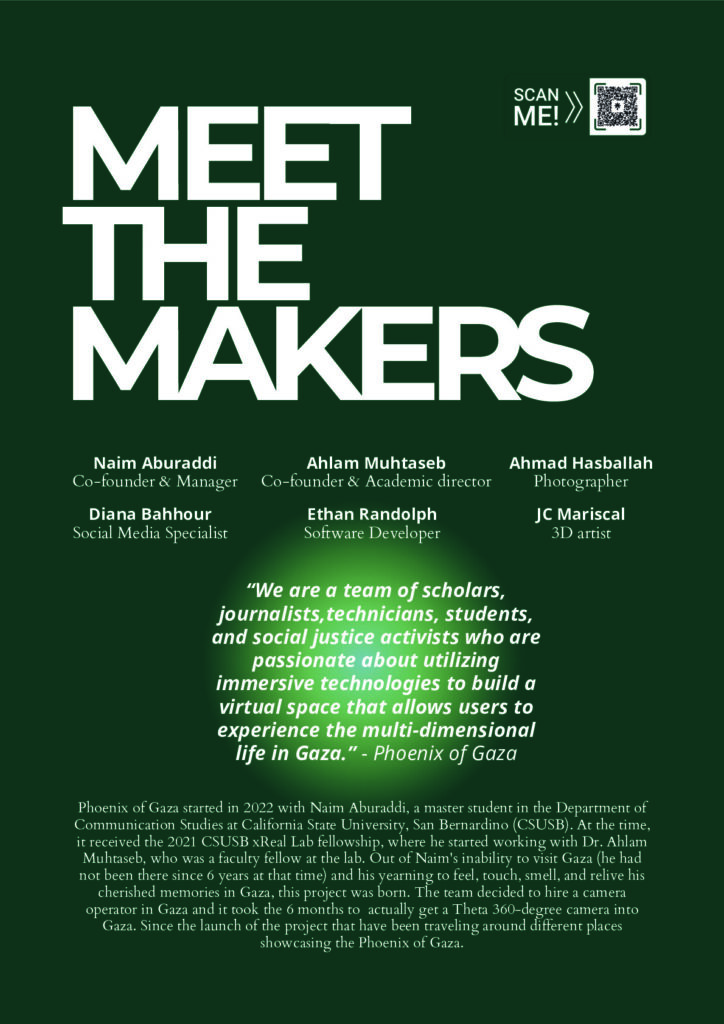

Phoenix of Gaza is a VR installation developed by a team of Palestinian-American scholars, activists, and journalists, capturing the untold stories of Gaza’s people and its transformation. The project was initiated in early 2022 by Naim Aburaddi, then an MA student in the Department of Communication Studies at California State University, San Bernardino (CSUSB). Aburaddi sought to reconnect with his homeland of Gaza, which he had not visited in six years. His goal was to capture and preserve the sensory and emotional experience of being in Gaza—its sights, sounds, and atmosphere. To achieve this, between July 2022 and July 2023, the Phoenix of Gaza team worked with local camera operators, amongst them *Yahya Sobeih, in Gaza with two aims in mind: to capture Gaza outside the realm of death and destruction and to show the multiplicity of Gaza, introducing the multi-dimensional realities there.

The Virtual Reality piece presents a 6DoF storyscape where the user is in emplaced within a 3D CGI-rendered version of the now-destroyed Pasha Palace. Through a point and click system, the user is free to roam the various quarters of the Palace, its structure was digitally recreated based on the footage the Phoenix of Gaza team shot there prior to its destruction. In this virtual model of Gaza, the makers then emplaced many happy and everyday moments. The palace’s rooms are filled with circular objects that transport the user to a 3DoF 360-video that captures some of the daily life in Gaza. Most of the footage was shot prior to the terror attack on October 7th 2023, capturing places that no longer exist today, such as bustling streets, markets and shops, fruit- and vegetable picking practices, a wedding, beach, stitching workshops, dabke dancing and different mosques spread throughout Gaza.

Phoenix of Gaza XR was built with the help of a team of technicians and 3-D designers from the xReal Lab at CSUSB. The makers write that they sought to “capture happy moments and mundane life activities; to show how people resist in their resilience and insistence on making life out of the brutal Israeli siege, they captured places and faces that no longer exist in the geography of Gaza. Second, we wanted to imagine a liberated Gaza in virtual spaces.” (Phoenix of Gaza website). Interspersed in the CGI-rendered palace space are bubbles that contain footage marked as ‘during the war’, which includes footage of some the same spaces only after the bombing began, as well as a footage of the people of Gaza continuing to make life under the current atrocities. There is no graphic war-footage, nor is there little in terms of music or narrative to nudge the user’s emotional response towards feeling a particular way. The effect is a piece that functions like a quiet archive of multiplicities of daily life in Gaza before the ongoing genocide. The makers conclude, “a project that was supposed to imagine a liberated Gaza turned into a heritage preservation one and documentary evidence of the genocide, taking into consideration that many of the places we captured had been on the UNESCO heritage list” (Pheonix of Gaza website).

The set-up

Over four days, approximately 60 visitors engaged with the Phoenix of Gaza VR installation. Due to the short timeline for coordinating with Movies that Matter, we needed to be flexible and creative with our setup. We hosted the installation in a foyer near the entrance of the Filmhuis—one of the festival’s main venues. Our objective was to find a balance between visibility and privacy, ensuring that participants could fully immerse themselves in the experience. The setup included three rotating bar stools, three VR headsets (two Meta Quest 3 and one Meta Quest 3s), three pairs of headphones, and three controllers. To provide context for visitors, we displayed four posters detailing the background of Phoenix of Gaza, its purpose, and the team behind the project. This introduction was important to us to ensure participants understood what Phoenix of Gaza was about, how it came about and who made, before beginning the experience. Therefore, we made sure that before putting on the headset visitors read the posters and received a brief introduction from us, including guidance on how to navigate the virtual environment.

The participants

The festival audience was diverse, including both international visitors—many from the Global South—and local attendees from the Netherlands. Age-wise, participants ranged from their early 20s to their mid-70s, resulting in varied levels of familiarity with VR technology. For many, this was their first VR experience, and some were initially uncertain about what to expect. To address concerns, we reassured participants that the experience did not contain violent imagery and that they had full control over what they viewed and when they chose to end the session. Navigating the experience presented a learning curve for some visitors, particularly when using the controller to move forward and select content. Many initially struggled with the interaction mechanics, either pressing buttons for too long or encountering virtual obstacles. Since we could not see what participants were experiencing inside the VR environment, we relied on their descriptions to assist them. Encouraging a patient and exploratory approach proved effective, and ultimately, everyone who wished to engage with the installation was able to do so. This made clear to us that the way we engaged with participants, actively shaped their experience of Phoenix of Gaza.

Additionally, we put a lot of attention on getting people properly into the experience and also carefully guiding them out of the experience again. Specifically, the transition from the virtual space to the festival room was an important moment to allow visitors to reflect on their experience and share their thoughts and feelings with us, if they wanted to. We also offered a table with pen and paper for visitors to share their reflections with us anonymously.

Participants feedback

After completing the experience—there is no fixed ending, as participants decide when to exit—we engaged in open-ended conversations about their impressions. We left those questions open because we wanted to give participants the opportunity to tell us whatever they wanted to share and what they felt most comfortable to share. It was noticeable that some people felt more comfortable to first – or only – engage with their experience of the technology. Some participants were primarily interested in discussing the technical aspects of VR, such as where in the digital space they had been or experiencing motion-sickness. A few visitors preferred not to share their thoughts, simply expressing gratitude for the opportunity to view Phoenix of Gaza. It gave a sense of wanting to keep the experience with themselves and not wanting to or being able to put it into words.

A recurring theme in participant feedback was the contrast between the VR experience and the dominant narratives of Gaza as seen in news media. Participants shared how eye-opening the experience was for them to see “normal life” in Gaza. Many were struck by the depiction of daily life, commenting on how it differed from the conflict-centred images often encountered on social media. Scenes of harvesting figs and olives, for example, were described as immersive and grounding, due to their everydayness. Other participants were especially touched by scenes of children playing, amidst the war and rubble of destroyed buildings. A recording of a large gathering at a mosque led some to reflect on the uncertain futures of the individuals captured in the footage. These responses highlighted the role of Phoenix of Gaza as an archive of everyday life, offering an alternative lens through which to engage with Gaza beyond crisis reporting.

Overall, participants responded very positively to Phoenix of Gaza and expressed appreciation for the opportunity to experience a different perspective. Many noted that the ability to control their viewing choices and immerse themselves in ordinary, day-to-day moments provided a meaningful contrast to the often abrupt and distressing images encountered in digital spaces. The project’s focus on the mundane aspects of life allowed for deeper and more accessible engagement and discussion with the participants about what they had seen and what it did to them, demonstrating the potential of VR as a medium for storytelling and education.

Conclusion

We come away from the experience of screening Phoenix of Gaza with the impression that what affects audiences in VR, what constitutes it as a ‘technology of feeling’, is in fact not any spectacular cinematic, narrative and audiovisual technique. Rather, it is the reflective moments afforded through spatial exploration done at one’s own pace and engagement with the narrative architecture within the VR (Kors et al. 2016). As a medium, VR momentarily becomes a totality, enveloping the ears and eyes of the audience and disconnecting them from hubbub of their own daily life, allowing a moment of total focus on the topic at hand from which one is unable to look, or indeed scroll, away. We found that it was the stillness of everyday footage, coupled with the stillness of simply spending time being with that footage, was what provoked for many in the audience a profound and intense experience. At the same time, we also found it was crucial as curators to move beyond the technology and the technical set-up alone. We aimed to set up a space with care for our audiences, considering the surroundings to ensure a calm, safe and quiet environment. Besides our best attempts, we noticed in moments of disruption, we found that much of the potential power of the piece was lost.

Our reflections of curating Pheonix of Gaza at Movies that Matter, also resonate with what Sandra Ponzanesi (2024) has concluded in her paper on VR and the crisis of empathy. Here she identified everyday mundane events as one of the most politically potent sites for VR to explore. She stresses that humanitarian VR “[…] often involves disaster tourism or poverty porn. It would be worthwhile to focus not on spectacular things but on ordinary problems […]” (Ponzanesi 2024, 41). Phoenix of Gaza is in many ways a testament to the power of VR as an archive of the mundane and a piece that, as many of the audience members echoed, ought to be witnessed by many more.

Literature

Kors, Martijn J.L., Gabriele Ferri, Erik D. Van Der Spek, Cas Ketel, and Ben A.M. Schouten. 2016. “A Breathtaking Journey. On the Design of an Empathy-Arousing Mixed-Reality Game.” In Proceedings of the 2016 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 91–104. Austin Texas USA: ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/2967934.2968110.

Ponzanesi, Sandra. 2024. “Post-Humanitarianism and the Crisis of Empathy.” In Postcolonial Theory and Crisis, edited by Paulo De Medeiros and Sandra Ponzanesi, 21–46. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111005744-002.

*Obituary for Yahya Sobeih

It is with a heavy heart and so much pain that we share the devastating news that our beloved colleague and photojournalist, Yahya Sobeih, was martyred in Gaza a few hours ago.

His brutal, senseless killing came just hours after he shared the news of the birth of his baby, Amirah. Surrounded by family and friends in celebration, he was killed by an Israeli airstrike on a restaurant full of civilians. His brother-in-law, celebrating with Yahya, was killed too following his wife, Yahya’s sister, who was killed last year. Yahya, like many Gazans, lost many members of his family due to the ongoing genocide.

The Phoenix of Gaza XR team is beyond devastated and heartbroken. We are still in disbelief and processing this news. The Phoenix of Gaza XR project began by capturing Gaza outside the realm of death and destruction and to show the multiplicity of Gaza. With Yahya and other team members, we encapsulated a side of Gaza that would never be seen in reality again.. As we continue this project, we will continue to honour the resilience and insistence on making life out of the brutal Israeli siege that Yahya and all the people of Gaza want us to see.

As we mourn, we ask how many more Palestinian lives will be taken away by the war on Gaza in a ruthless and senseless genocide that the world is watching, funding, supplying, and allowing to continue? How many more? Our U.S. tax dollars killed Yahya, over 200 journalists, and the tens of thousands of innocent souls in Gaza through weapons sales accompanied by logistical and political support.

May you rest in power, dear Yahya. We couldn’t have done the work we do without your bravery and dedication. You will be truly missed.